BACKGROUND

Dr. Beheruz Sethna shares his experiences of his first days in the United States as he struggled to survive in New York City with only 100 dollars in his pocket. Despite his early "starvation days" at Columbia University, Dr. Sethna became the first person of Indian heritage to serve as president of an American university.

TRANSCRIPT

My name is Beheruz Sethna and I came to the United States to do a PhD at Columbia University. In those days, India didn’t allow you to take much money out of the country. Now, I came from a family from very modest means so I couldn’t have brought very much either, but I had only about---I’m trying to think---about a hundred dollars with me. Now I came to Columbia on a scholarship so I thought that all of that would be fine, but I had some rude awakening there.

Columbia had given me a very—what I believe—a very generous scholarship. So I go to Columbia and present my passport and so on and so on and I say, “Can I have the money?” I told them this, I said, “I really don’t need the loan. Just give me the grant component and I’ll be just fine,” and they said, “ No, you can’t do that. I can’t give you the grant if you don’t take the loan.” And that in itself would not have been a problem except there was some phrase in that material. It was called a co-maker. You had to have a co-maker for the loan component, which was basically someone—an American—had to sign for that. Be a co-signer if you like. So, as I said, I didn’t look at the loan part closely at all and in any case I didn’t understand the phrase “co-maker.” So it was all explained to me and then I was in deep trouble because I didn’t know anybody in America and you can’t just stop a passing American and say, “Would you sign a loan for me?” (laughs) You can’t do that.

So I was---I didn’t know what to do. And so, for my entire first semester, I basically had no money. Now, the very next day I moved out of international house and I started looking for a place close to Columbia that I could stay for a much smaller budget. And I actually found a little old lady who would rent out a room for eight dollars a week. And believe me, it was an eight dollars a week room! (laughs) I have been a boy scout and so on and slept in various camping sites and things like that but that bed had lumps in it that you wouldn’t believe and…you know, it was really an eight dollar room! (laughs)

And it was extremely tiny and extremely uncomfortable, but I really couldn’t afford anything more. I did that and then had to find a way to eat because again, I had no money. I had that one hundred dollars and I had to figure out a way to eat. So I literally went through the first semester living on, you know, less than a dollar day. I pretty much starved. I would buy the cheapest can of food I could find and so I would have half a can between two slices of bread for lunch and the other half of the can for dinner. And I lived that way for several months. If anyone ever visited from India, I would eat like a king because they knew…anyone visiting from India knew that you gotta take this guy to lunch or dinner because he’s dying over there (laughs).

One day when I was in the grocery store---and of course, I didn’t know at the time anything about how grocery stores were organized or anything of that kind. So it was all a new experience to me and one day wandering in a different section of that store, I saw a can that a picture of some meatballs on it and it was instead of serving 45 cents, it was something like 35 cents. So I said, “Oh boy, this is really good.” So I filled the cart up with those less expensive cans and went to check out and fortunately something in the back of my mind said, “Well, maybe I should taste one first and then do this.” So I bought only one can. Fortunately I had the good sense to that. That night I said, “I’m gonna eat really well. At least tonight I’m gonna eat the whole can.” And I opened this can and an awful smell emerges from there. So I said, “What on earth is this?” And it was at that time I looked at the can a little more closely and there was a picture of a dog on it. So this was dog food that I had bought (laughs). And so, I’ll you how hungry I was, I almost thought that I’m going to have this, but I didn’t. I mean, I almost had it, but I didn’t. So that night I went to bed hungry. I didn’t have the can of food to eat.

The academic part of it though was great. I mean, things went well, got good grades, made good progress, and I decided that I was going to concentrate on academics. And so, you know, it was a very, very focused thing that I concentrated exclusively on academics and I did well. I did well at Columbia, so that was a good thing.

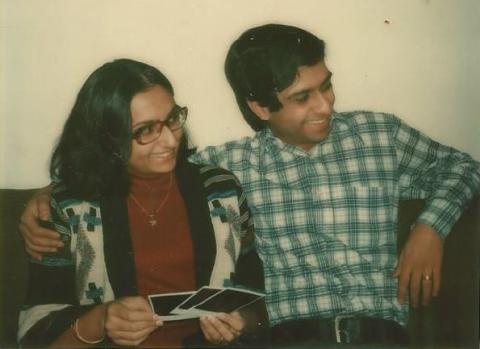

But then at the end of that entire academic year, I went back to India and got married and then brought my wife here and then we had more money and then we had an apartment to stay in and so on. After that, it started improving.

But the one thing I wouldn’t want to leave this interview without saying is that I really believe I could not have done what I have been fortunate enough to do were it not for my parents. Not only the sacrifices they made, but the expectations that they had for me. I was not a—by any means, a brilliant student in high school. The vision my father had and my parents had for me was to get an absolutely top-notch education. They really believed in the value of education. So I really have no problem A) giving them credit for what I have been able to accomplish and B) to tell students of today here in America that pushy parents are not a bad thing. So listen to your parents.